William Buckland

Child and student 1784-1808

William Buckland was born in Axminster, Devon, on 12 March 1784, the eldest son of Charles Buckland, Rector of Templeton and Trusham, and his wife Elizabeth.

"The first cause of Dr. Buckland’s attention to fossil organic remains was the fact, that near his birthplace at Axminster were large quarries of lias, abounding in fossil organic remains. His father … took great interest in the improvement of roads, &c., and was accustomed to take his son with him on his walks; from the above-mentioned quarries both father and son collected Ammonites, and other shells, which thus became familiar to the lad from his infancy."

At first Buckland was educated at home under his father’s instruction, and at Axminster School, but in 1797 he entered Blundell’s school in Tiverton. A year later, taking advantage of family contacts (as was quite usual at the time), Buckland’s father was able to secure for his son a scholarship to Winchester College. There, William progressed well enough through the narrow formal education intended to better prepare him for university entrance, while continuing, in his spare time, to develop his interest in natural history. In 1801, with the help of some coaching from his uncle, he won a scholarship to Corpus Christi College, Oxford, and thus began his Oxford career.

Buckland went on to obtain his MA degree and in 1808 became a priest and a fellow of his college the following year. During this period, he augmented his income by coaching students and had sufficient funds and time on his hands to expand his own scientific interests. He attended the lectures of Sir Christopher Pegge on anatomy and those of John Kidd on mineralogy and chemistry. Kidd took his students on regular field excursions into the Oxfordshire countryside and these played an important role in turning Buckland’s enthusiasm for fossil collecting into a more serious interest in geology.

Buckland the Geologist 1810-1825

From about 1810, during the long university vacations, Buckland made frequent geological excursions on horseback to various parts of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. He was searching for field evidence which was then being brought together to establish the geological succession of strata in England.

"He rode a favourite old black mare, who was frequently caparisoned all over with heavy bags of fossils and ponderous hammers. The old mare soon learnt her duty, and seemed to take interest in her master’s pursuits; for she would remain quiet without anyone to hold her, while he was examining sections and strata, and then patiently submit to be loaded with interesting but weighty specimens. Ultimately she became so accustomed to her work, that she eventually came to a full stop at a stone quarry, and nothing would persuade her to proceed until the rider had got off and examined (or, if a stranger to her, pretended to examine) the quarry."

In 1813 Kidd resigned as Reader of Mineralogy, and Buckland was appointed his successor, delivering his lectures in the Old Ashmolean building in Broad Street (now the Museum of the History of Science). From the outset, Buckland sought to introduce increasing amounts of geology and palaeontology into his lectures, which were, by all accounts lively events and always popular, not only with students but also senior members of the university.

Engraving of the Old Ashmolean Museum. © Museum of the History of Science

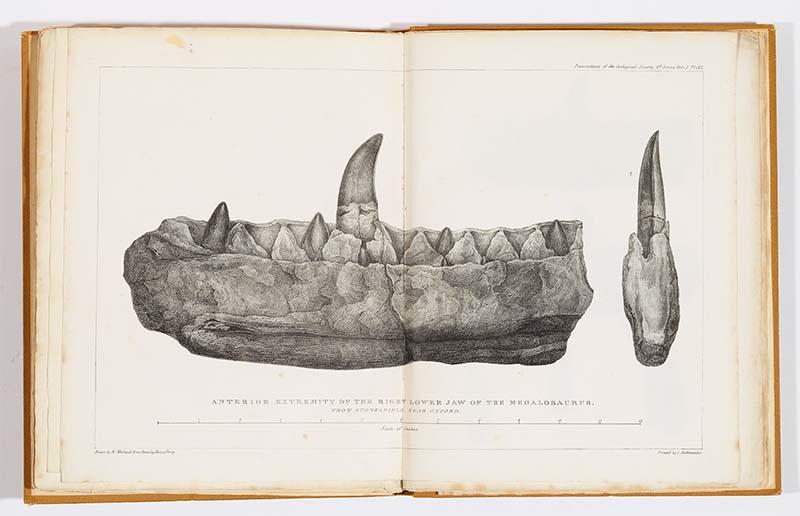

In 1816 Buckland began his European tours, which would eventually take him to Germany, Poland, Austria, Italy, Switzerland and France. In the course of his travels, he brought to the museum large and valuable collections, and to the geologists of England observations of phenomena then little known to them. He also became acquainted with other European scientists. In 1818 Georges Cuvier, Director of the French Natural History Museum, visited him in Oxford and was shown a collection of enormous bones from Stonesfield. These bones, later named Megalosaurus, or 'great lizard' by Buckland on account of its vast size, were to form the basis of one for the most important scientific papers of Buckland’s career.

In 1818 Buckland persuaded the Prince Regent to endow a second Readership, this time in Geology, which he could hold in addition to his mineralogical appointment. He delivered his inaugural address on 15 May 1819; it was subsequently published in 1820 under the title of Vindiciae Geologiae; or the 'Connexion of Geology with Religion Explained'. The aim of the lecture was to justify the inclusion of the new science of geology alongside the established studies of the University, but the compatibility of geological evidence with biblical accounts of Creation and the Noachian Flood was also addressed. Buckland set out the facts as he saw them, noting clear evidence for a universal deluge, and introducing the hypothesis that the word "beginning" as used in Genesis expressed an undefined period of time between the origin of the earth and the creation of its current inhabitants, a period during which a long series of revolutions had occurred with successive creations of new plant and animal groups.

Paviland Cave, South Wales

For the next few years, Buckland developed his understanding of the supposed deluge, as seen in his 1822 account of the fossil bones (elephant, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, horse, ox, deer, hyaena, tiger, bear, wolf, fox, rodents and birds) found at Kirkdale Cave in Yorkshire. Until this time, it was commonly assumed that such remains were testimony to animals that had perished in the Flood and been carried from their original homes in the tropics by the surging waters. To Buckland, however, the great quantity of hyaena remains and the splintered state of all the bones pointed to a quite different conclusion—that the cave had actually been inhabited by hyaenas in antediluvian times, the effect of the Flood being no more than to cover bones already present with a layer of mud.

Satirical drawing of Buckland entering Kirkdale cave

By 1823 this account had been expanded into a full-scale treatise on Buckland’s cavern research, Reliquiae Diluvianae, or, 'Observations on the Organic Remains attesting the Action of a Universal Deluge', in which he argued that the remains of animals found in caves provided clues as to the inhabitants and character of the earth before the Great Flood recorded in Genesis. The book sold rapidly, and recognition of Buckland’s achievement was widespread.

One of Buckland's geological lectures, 1823

By 1824 Buckland has established a new lecture room and museum dedicated to geology on the raised ground floor of the Ashmolean where he displayed the substantial collection of specimens that he had amassed, including many spectacular fossils. This attracted much attention and as he himself explained, "being [unofficial] Curator of the Collection and shewman of it, or private lecturer to every stranger, foreign or domestic, that comes to Oxford … I have also to shew hospitality to such strangers and to hold constant correspondence and exchanging of specimens with foreigners of all countrys … also to give private instruction to young men travelling abroad, or relating to their own property at home."

At the same time, he was continually adding to his own large collection of rocks, minerals and fossils, which he kept in his rooms in Corpus.

Despite his success, financial remuneration for Buckland’s work remained modest and, for the moment, he continued to live in college. Roderick Murchison thus describes a visit paid to Buckland’s rooms in the winter of 1824-5: "On repairing from the Star Inn to Buckland’s domicile in Corpus Christi College, I can never forget the scene which awaited me. Having, by direction of the janitor, climbed up a narrow staircase, I entered a long corridor-like room … which was filled with rocks, shells and bones in dire confusion, and in a sort of sanctum at the end was my friend in his black gown looking like a necromancer, sitting on the one only rickety chair not covered with fossils, and cleaning out a fossil bone from the matrix."

In 1824 Buckland became President of the Geological Society, and it was at his first meeting in this office that he finally announced the discovery of his Megalosaurus bones at Stonesfield. His final paper on this was published later that year, and forms the first full account of what would later be called a dinosaur. The bones Buckland studied are now on display in the Museum.

The Megalosaurus jaw studied by Buckland

The Megalosaurus jaw illustrated by Mary Morland

Canon of Christ Church 1825-1836

In 1825 Buckland resigned his college fellowship and accepted the living of Stoke Charity in Hampshire. However, he failed to take up the appointment, for a few months later he was made a Canon of Christ Church, then one of the richest governmental rewards for academic distinction. In December Buckland married Mary Morland of Abingdon, Oxfordshire, a studious and accomplished young woman with whom he had many interests in common. In addition to being a collector in her own right, Mary was a skilled draughtswoman and had contributed illustrations to Cuvier’s prestigious works and to Buckland’s own publications, including his Megalosaurus paper (see above). Though only 28 at the time, Mary was already an accomplished draughtswoman and collector of fossils, and had contributed illustrations to the works of both William Conybeare and George Cuvier. Their shared passion for geology is evident in their honeymoon tour, which lasted a year and included visits to many famous geologists and geological locations in France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Italy and Sicily.

Buckland and his wife had a large family—nine children, five of whom survived to adulthood. The eldest son, Frank, gives the following account of his mother and her contribution to Buckland’s work: "Not only was she a pious, amiable, and excellent helpmate to my father; but being naturally endowed with great mental powers, habits of perseverance and order, tempered by excellent judgement, she materially assisted her husband in his literary labours, and often gave to them a polish which added not a little to their merit … Not only with her pen did she render material assistance, but her natural talent in the use of her pencil enabled her to give accurate illustrations and finished drawings … She was also particularly clever and neat in mending broken fossils … It was her occupation also to label the specimens."

Two years after their marriage, the polymathic Scottish clergyman, the Rev. Henry Duncan, sent a slab of sandstone with impressed footprints to Buckland to decipher. As Frank relates, "Buckland was greatly puzzled; but at last, one night, or rather between two and three in the morning, when, according to his wont, he was busy writing, it suddenly occurred to him that these impressions were those of a species of tortoise. He therefore called his wife to come down to make some paste, while he went and fetched the tortoise from the garden. On his return he found the kitchen table covered with paste, upon which the tortoise was placed. The delight of this scientific couple may be imagined when they found that the footmarks of the tortoise on the paste were identical with those on the sandstone slab."

During the 1820s Buckland greatly developed his friendship with another talented woman, Mary Anning, the fossil expert resident at Lyme Regis in Dorset. She often informed Buckland first of her important discoveries which he published, while at the same time assisting her to find buyers. A cast of one of her most spectacular finds, a massive near complete extinct marine reptile, a plesiosaur, later graced the wall of his lecture room and can be seen in the Museum today. Buckland’s friend, the Duke of Buckingham had bought the original specimen from Mary Anning in 1824.

Buckland continued to give his annual courses of lectures in geology and mineralogy, but his working environment was about to change. Until this point the Ashmolean’s laboratory and lecture rooms had fulfilled the University’s requirements in the teaching of natural sciences, but the explosive development of these disciplines in the early decades of the nineteenth century rapidly led to the need for new and greatly expanded facilities in this field. Between 1830 and 1832 the geological and mineralogical collections, together with their professor, were progressively removed from the Ashmolean to more spacious quarters in the adjacent Clarendon building.

In 1836 after five years of hard work Buckland published his contribution to an important series of scientific treatises commissioned by Lord Bridgewater intended to prove "the Power, Wisdom, and Goodness of God as manifested in the Creation". Buckland’s volume, 'Geology and Mineralogy', covered similar ground to his Vindiciae Geologiae of 1820. It was, however, much larger, forming a compendium of the latest geological and palaeontological science and was written in an accessible style aimed at the general reader. As a firm believer in the efficacy of visual communication, Buckland also commissioned illustrations to explain his text. These were so numerous they formed an entire second volume to his work and ensured that his readers had the opportunity to grasp the complexity of his arguments in a manner not unlike that of his lecture students.

The scientific celebrity 1837-1844

By 1837, Buckland had attained a high position in the scientific world beyond Oxford. The Royal Society, the British Association, and the Geological Society all provided him with a forum, and he was prominent in support of agricultural, civil engineering, and archaeological societies. He lectured, entertained, and travelled widely, and his friendship with the Tory prime minister Robert Peel gave him access to a wide and influential circle. With Adam Sedgwick and Charles Lyell, he prepared the report that resulted in the formation of the Geological Survey of Great Britain, and he also helped towards the establishment of the School of Mines and the Mining Records Office.

Around this time, Buckland at last proposed a new explanation for some of the geological phenomena which he had previously attributed to the Great Flood. In 1838 he travelled to Switzerland to meet Louis Agassiz and to examine for himself the polished and striated rocks and transported material that Agassiz had attributed to the agency of glaciers. Although sceptical at first, Buckland soon found the evidence overwhelming and became an enthusiastic convert to the theory. Moreover, he began to recognise direct parallels between the glacial phenomena of Switzerland and similar phenomena he had observed in Scotland, Wales, and northern England.

Buckland dressed for the Glaciers, 1841

In 1840, Agassiz came to Britain for the Glasgow meeting of the British Association, at which he described the action of glaciers and the deposits associated with them, before accompanying Buckland on an extended tour to examine the evidence for former glaciation in Scotland. They returned to London to present their findings to the Geological Society, of which Buckland was again President. Despite the powerful arguments put forward by the two men, the response from the Society was almost uniformly hostile. Nevertheless, Buckland was satisfied that he had found the true origin of many of the surface deposits covering Britain.

Needless to say, Buckland’s growing family continued to play a large part in his life, as described by his daughter Elizabeth. Buckland "was a kind and affectionate father, and always liked to have his children about him … The young people were always presented to the numerous learned foreigners and illustrious travellers who came to Oxford to see the Professor’s world-famed collection of fossils and bones at the Clarendon; and at dessert in the evening they were told, shortly and graphically, what these great men were famous for."

During the 1840s, Buckland began to show increasing signs of eccentricity. He used to say, for example, that he had eaten his way through the animal kingdom, and guests attested to the many curious delicacies served at his table. John Ruskin, for example, always regretted having to decline an invitation to attend one of the Buckland family breakfasts at which he “missed a delicate toast of mice”. If the stories that built up around Buckland at this time are held to be true, this propensity may have got a little out of hand at times, as related by the famous raconteur Augustus Hare: "Talk of strange relics led to mention of the heart of a French King preserved at Nuneham in a silver casket. Dr. Buckland, whilst looking at it, exclaimed, ‘I have eaten many strange things, but have never eaten the heart of a king before,’ and, before anyone could hinder him, he had gobbled it up, and the precious relic was lost for ever."

Dean of Westminster 1845-1856

In 1845, much to his surprise, Buckland was appointed Dean of Westminster on the recommendation of his friend Robert Peel. He immediately instigated repairs to the abbey and the school and was determined to make the school an effective modern educational institution. Rising soon after seven, he worked incessantly until two or three o’clock the next morning, allowing himself scarcely any time for meals and still less for recreation; yet despite his important duties, he still found time to travel between Oxford and Westminster to lecture on his favourite science.

William Buckland, c.1845

Despite his continuing passion for geology, Buckland seems to have lost heart in the battle to establish it as a formal part of the university curriculum. In 1847, he refused to add his signature to a document prepared by some of his scientific colleagues requesting a building to house natural science teaching collections and provide proper laboratory facilities. His refusal was less from lack of regard than from despair, stating, "Some years ago I was sanguine, as you are now, as to the possibility of Natural History making some progress in Oxford, but I have long come to the conclusion that it is utterly hopeless."

With his appointment as Dean of Westminster came the living of Islip, a village seven miles from Oxford. Here, Buckland laid out allotments for labourers, conducted agricultural experiments, fitted up a recreation room for the village lads, started a night school, and preached earnest, practical sermons adapted to the needs of his rural congregation. Meanwhile, in the village school, "Mrs. Buckland taught boys geography and the use of globes which she had made from paper and inflated, showing them at the same time... the homes of foreign products and supplying specimens of the sugarcane, the tea tree and other articles of daily use."

Towards the end of 1849, Buckland contracted a debilitating illness marked by apathy and depression. His doctors recommended the quiet and fresh air of Islip, and the garden and allotments seemed to cheer him for a time, but his symptoms worsened. He lingered on in poor health for seven more years before dying on 14 August 1856. His final geological jest was revealed when the grave-digger came to excavate his reserved plot in the local graveyard — an outcrop of solid Jurassic limestone lay just inches below the surface. Explosives had to be used to dig the grave, reminding all who heard of Richard Whatley’s 1820 Elegy intended for Professor Buckland:

Where shall we our great Professor inter

That in peace may rest his bones?

If we hew him a rocky sepulchre

He’ll rise and break the stones

And examine each stratum that lies around

For he’s quite in his element underground.